Twelve years ago, the leaders of the world’s nations descended on Copenhagen for a key UN climate summit in the hope of securing a new worldwide agreement on addressing the growing threat of global warming.

It ended in failure and subsequent years marked a reversal of the progress science had made up to 2009 in getting the world to wake up to the imminent risks of the climate emergency. Now, following recent years of frequent extreme weather, as well as a pandemic many have linked to man’s neglect and destruction of the natural world, the COP26 UN climate conference in Glasgow later this month presents the world with another chance – possibly its last – to set a course of action that can ensure disaster is averted later this century.

With climate and the pandemic very much at the forefront of thinking, the fifth Healthy City Design International Congress opened with an outstanding keynote plenary session, which touched on timelines both at the planetary health level and in the context of ageing populations and living longer in good health.

“Our theme for 2021 is back from the brink and, boy, did we stare into the abyss during the pandemic,” remarked co-founder Jeremy Myerson in his introduction. “Cities were emptied, working patterns and supply chains disrupted, and urban communities came under unprecedented pressure . . . That’s why, this year, we’ve decided to focus the Congress on the fight-back – on ways that urban planners, architects, policymakers, and public health professionals can pick up the pieces and formulate new ways to design the post-pandemic city.”

The road to COP26: regenerative architecture for health

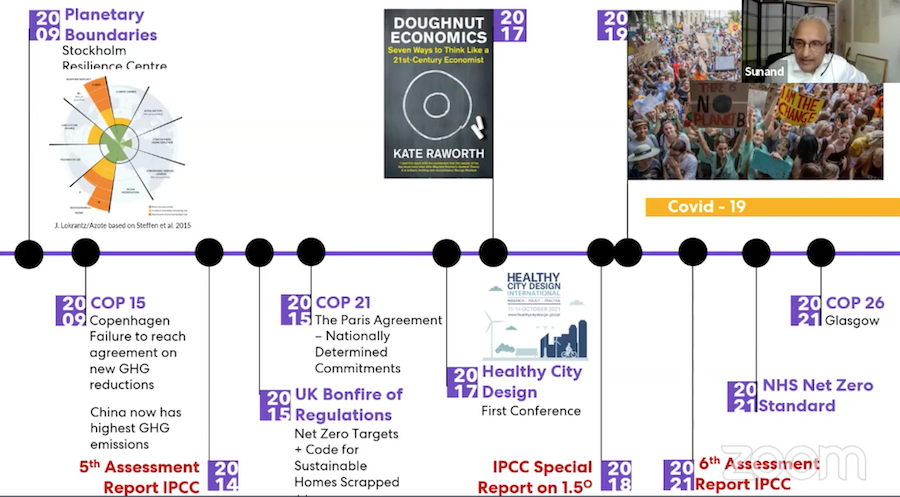

The COP15 conference in Copenhagen featured on a timeline of progress on climate and health issues presented by UK Green Building Council chair and principal at Perkins&Will Sunand Prasad.

Through the timeline, he highlighted the limits of reason: “People have been explaining the rational arguments on these issues for a long time, but we don’t necessarily listen and take it in,” he said. “How is it that we will transcend reason to reach everyone’s hearts and minds?

The 1972 OPEC oil crisis was a key point, which attracted public attention about finite resources. “Resource limitation and the need for recycling, reusing and repurposing our entire environment were probably the first things that caught the imagination,” he said, “rather than the arcane science of regulatory enforcing of atmospheric aerosol concentrations.”

As nations and leaders began to take notice, the 1980s and 90s saw more international conventions discussing these issues, with mixed results in reaching consensus. The big lesson from this, said Prasad, is that national and international action “will always be disappointing. We have lived through these disappointments, and they’ve been hugely well articulated by Greta Thunberg, but the hope lies in local action in cities. And cities, local action and individual initiatives are always inspiring.”

In 2000, the UN agreed the Millennium Development Goals, with 191 countries signing up. These had the aim of reaching environmental sustainability by 2015, leading Prasad to lament: “We should have done this six years ago, if international targets and fine words actually had any real meaning.”

He added: “If the cost is great, and the science is not quite there, and vested interests are not threatened, we would get there easily. We do know a lot about the ‘how’. But the big frustration is that it genuinely doesn’t suit many vested interests.”

We’ve reached a point now, however, when, according to Prasad, business and insurance firms are starting to cotton on that they need to act, and the IPCC Special report in 2018 on 1.5 degrees has “flicked that final switch” with the warning that we’ve now got just 12 years left to bring this under control.

There are signs of real progress. The UK’s emissions are now about 40 per cent below what they were in 1990 while GDP growth has been sustained, and among the flurry of initiatives is the NHS’ forthcoming Net Zero standard for hospitals. “If we can do that for hospitals, then we can do that for other buildings – for cities, for transport, and to create a really healthy city,” said Prasad.

But there is much work to do on ensuring equity and inclusion on these issues, he added, reflecting that “the people who are most impacted by climate change are some of the poorest and most vulnerable people in the world, and they’re some of the least engaged in doing something about it. They need to be at the table.”

Design for planet

Prasad’s comments chimed with Minnie Moll’s insights on ‘Design for planet’, a new initiative launched by the Design Council, of which Moll is chief executive, and which aims to galvanise and support the 1.69 million people in the UK design economy to get design to be regenerative and not destructive.

Quoting Elvis Presley – “a little less conversation, a little more action please” – she argued that the biggest challenge we currently face is the ‘how’, because that’s where the blockages lie.

“What’s stopping us doing the things we need to do,” she said. “The challenge of achieving joined-up thinking, the challenge of getting multiple stakeholders aligned. The silos in local authorities and government; planning regulations; old and entrenched views; nimbyism; and, of course, the lack of investment and resources. These are things that kill innovation.”

“What’s stopping us doing the things we need to do,” she said. “The challenge of achieving joined-up thinking, the challenge of getting multiple stakeholders aligned. The silos in local authorities and government; planning regulations; old and entrenched views; nimbyism; and, of course, the lack of investment and resources. These are things that kill innovation.”

And referencing American doctor and writer Mark Hyman’s observation that “the power of community to create health is far greater than any physician, clinic or hospital”, she touched on the importance of grassroots initiative.

“The best placemaking is people-centred and place-based,” she said. “The magic happens locally and it has to involve communities. So local government, local stakeholders, and local community are key to designing net-zero and resilient cities.”

As Prasad also noted, we do have the knowledge and technology to move towards and achieve net zero, and Moll offered two examples to illustrate this fact. First, that we are apparently close to being able to pump hydrogen through our existing gas system network as a viable energy alternative. Second, that Coventry is exploring the feasibility of using technology in the roads that would enable electric vehicles to be charged as they are in motion.

But government also needs to play its part, she said: “Government must have a vision and a plan, and policy is not a plan. They must incentivise positive action, and, critically, they need to address some of the current disincentives. It cannot be more cost-effective, as it is currently, to knock down a building rather than refit it.”

The ingredients to this new mentality of designing for planet include, in Moll’s view, great vision, strong leadership, genuine and selfless shared purpose, unprecedented levels of collaboration, authentic co-creation, and real belief in inclusion to ensure a just and fair transition.

“Covid proved just how quickly we could do things when it’s not business as usual, and we must not accept going back to the slower timeframes for making change happen,” she said. “If we get these things right, I have no doubt that we can design for planet and, in doing so, create healthy and sustainable cities, and a just and fair transition for all.”

In ending, she offered another quote and a question from two prominent figures of the civil rights movement in America – first, Malcolm X, who said: “When I is replaced by we, even illness becomes wellness.” The question, attributed to John F Kennedy: “If not us, who; if not now, when.”

Designing the environment for living longer better

Much of the climate conversation in design and planning also revolves around the importance of systems thinking – the idea that cities are complex ecosystems – and systems thinking as a mindset is also relevant in population and preventive health, to encourage people to remain active and healthy as they age.

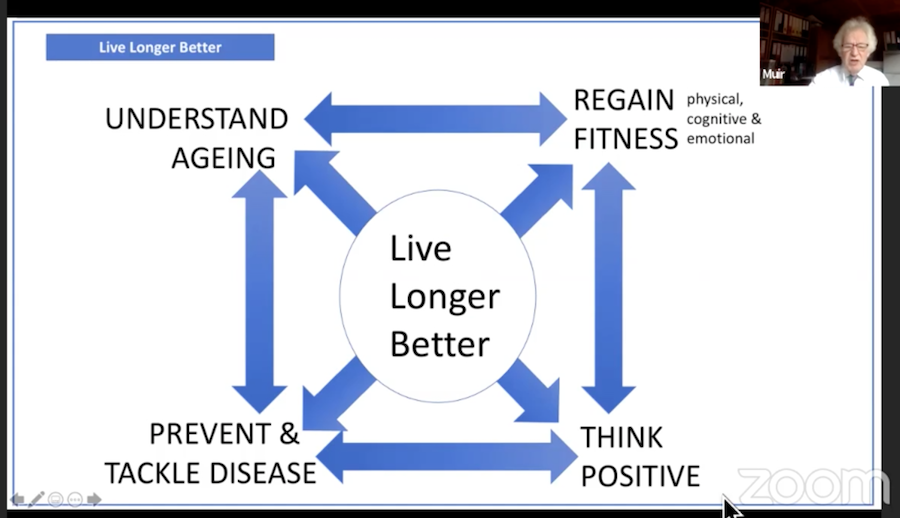

As Sir Muir Gray put it in his keynote address: “We need to get people to understand systems, networks and culture.”

Using the tidal wave as a metaphor for the ageing population timebomb accelerating towards us, Sir Muir noted that the number of people aged over 80 is expected to double in the next decade. Ageing, he said, is not a cause of major problems until people reach their 90s, but it does affect maximum ability and resilience.

Three processes are taking place – the first of which is loss of fitness. “Until recently the medical community has confused ageing and fitness,” he said. “The good news is that at any age you can narrow the fitness gap. The second thing that affects us as we age is disease. Not because ageing causes disease but because we live longer in a certain environment. The fitness gap widens after the onset of disease because of negative thinking. And the third process is ageism – negative thinking, pessimistic attitudes.

“We need to change by understanding ageing, preventing and tackling disease, regaining fitness, and thinking positive.”

And to turn the tidal wave metaphor on its head, a “Living Longer Better Revolution” is needed, delivered through a programme designed to achieve three things.

“The first aim,” he said, “is to increase activity, physical, cognitive and emotional, which will help people feel and function better, this year; prevent or delay the onset of dementia, disability and frailty; and focus on the three Rs – regain what they lost during lockdown, recover the strength, stamina, suppleness and skill they have lost in the last decade, and recondition the body that disease and inappropriate inactivity have deconditioned.”

A second aim involves increasing healthy life expectancy and compressing the period of dependency. And the third aim is to reduce the need for health and social care.

Pointing out that the programme is delivering networks at different levels – the level of the county or the city; more local district networks; and at the hyper local level – he concluded: “The networks give leadership, and the job of leadership is to change culture. We need a cultural revolution, away from a culture of care to a culture of enablement and coaching. And we need development of a new language – as language changes culture.”

“How do we achieve the aim of living longer better?” he asked. “Not by another reorganisation of the NHS,” he responded, “but by systems thinking. We need a system for living longer better.”