Often hailed as the “traffic-calming guru”, urban planner David Engwicht defines the role of transport as one of maximising trade: “The reason we invented cities is for exchange – goods, culture, friendships and knowledge – and to minimise travel.”

So where did it all go wrong? At some point, it seems, our over-reliance on the private car began to create more barriers for exchange, reducing opportunities for social engagement – perhaps an example of the law of diminishing returns in action.

“If we design only for the car, we’re not going to have very good economies,” said Dan Burden, director innovation and inspiration at Blue Zones, in his keynote address at Healthy City Design International. “One thing the pandemic has brought us is a catalytic effect where we’re starting to try out some ideas that we thought would be only temporary. And we’re finding that if we can convert streets back to the primary function of cities, then everyone is going to be healthier and we’re going to have better budgets to maintain.”

Urban designer and author Julie Campoli argued in her book Made for Walking that if we focus on the right density and the right qualities, the diversity, the distance to transit, accessible destinations for all, and design and parking, we can improve health and liveability in the city. And Burden pointed to Disney’s Magic Kingdom theme park as an example of exhibiting five key principles to successful cities.

“When you go to the Magic Kingdom, you feel secure, everything is convenient, there is an efficiency, there is a strong sense of comfort, and it’s welcoming,” Burden said, before broadening the discussion to outline some of his “baker’s dozen” of healthy city design principles and models.

One idea gaining in popularity is the idea of compact living centres – with Burden describing the five-minute walking radius as “the most time-honoured, basic tool to build walkable, liveable cities” and in “perfect alignment with Blue Zones Life Radius”.

Another important relationship to consider is the link between land use and transportation. According to Burden, at five or fewer automobile trips per day, much more urban space can be devoted to nature and green space, but when the number of trips gets to around ten per day, there is the same number of residential properties but most of the remaining space is taken up by parking, retail, and the built environment – all at the expense of nature.

Referencing the work of another urban designer, Donald Appleyard, on the speed of traffic, Burden noted the importance of light and low-speed traffic in creating more friendships and associates. “When there is heavy traffic, people only consider home territory to be their own house,” he said, “whereas with light traffic, they feel connection with the whole street as their home.”

Design elements such as greenery, buffers to the sidewalk, parking, and roundabouts can bring traffic speeds down and create the right social engagements and mix.

“Inclusive, lively public places are social glue,” he concluded. “Reclaiming the road for the public realm creates space for social engagement, friendship, and the relationships that everyone needs.

“Unprecedented collaboration” in designing healthy cities for all

The car also featured heavily in architect and urban designer Ken Greenberg’s keynote, which highlighted how the post-war American Dream, which was seen as an antidote to the disease and overcrowding conditions of the Industrial Revolution, also led to unintended consequences impacting health, owing to an over-dependence on the private automobile.

“In a couple of generations, we changed the face of the city from lively active sidewalks to forlorn arteries lined with parking lots where human beings were not meant to be on foot,” he said.

“We affected the environment, induced climate change, and created conditions of congestion that were unbearable. We compromised out health in terms of diabetes, obesity, heart disease and hypertension, particularly among young people in ways we didn’t anticipate.”

Covid-19, said Greenberg, has shone a bright light on the daunting challenges we were already facing prior to the pandemic – including mobility, ageing infrastructure, climate change, affordability, vulnerable populations, and lack of public space. And all these things are connected, with climate change impacting human health through respiratory diseases, water-borne outbreaks, the ability to move in the city, etc. Maps of Toronto, he observed, which highlight the link between the lack of walkability, Covid-19, and vulnerability, are virtually identical to those showing the lack of walkability and levels of chronic and infectious disease among the population.

Covid-19, said Greenberg, has shone a bright light on the daunting challenges we were already facing prior to the pandemic – including mobility, ageing infrastructure, climate change, affordability, vulnerable populations, and lack of public space. And all these things are connected, with climate change impacting human health through respiratory diseases, water-borne outbreaks, the ability to move in the city, etc. Maps of Toronto, he observed, which highlight the link between the lack of walkability, Covid-19, and vulnerability, are virtually identical to those showing the lack of walkability and levels of chronic and infectious disease among the population.

Listing the urban design implications from the pandemic, which point the way to healthier cities, Greenberg noted that density is not the enemy; density done right is the solution; affordability is critical; equity is resilient; micro-communities can be formed from social networks; learning can be gained from ‘improvised’ pilots; new ways should be embraced to move in the city; and public spaces are critical.

And in describing work carried out nearly 20 years ago on a masterplan for the revitalisation of Regent Park, Greenberg explained how there was a realisation that the physical plan was no more important than the social development plan and tenant relocation plan, and other elements that dealt with aspects of people’s lives beyond the housing units. The outcome has been to address isolation and provide a boost to social engagement.

“In the first phase of the project, we insisted on implementing the full DNA of the social complexity and mix, including market housing, seniors’ housing, affordable housing for families, and a grocery store, which had been missing in the community and we saw as a key ingredient for success,” he said.

“Massive revitalisation effort has brought many more facilities to make the neighbourhood a destination of choice for the city – for example, an arts and cultural centre, a swimming pool, sports, health facilities, a birthing centre.”

Referencing 20th century American-Canadian journalist, author, theorist and activist Jane Jacobs, who observed that cities have “the capability of providing something for everybody, only because and only when they’re created by everybody”, Greenberg concluded that delivering on this aspiration demands “an unprecedented level of collaboration to design healthier and sustainable cities”.

Dementia and a life worth living

Both Greenberg’s and Burden’s talks also held a strong alignment with John Zeisel’s keynote address, which called for the need “to start investing in social planning and infrastructure to enable social integration”, in the context of ageing populations and growing numbers of people with dementia.

Stripping it down to numbers, the problem is startling. According to Zeisel, president of Hearthstone Alzheimer Care and founder of the I’m Still Here Foundation, the ageing dynamics mean that by the middle of the century there could be 25 per cent of the population over the age of 65, 12.5 per cent living with dementia, and 12.5 per cent or more living with mild cognitive impairment. “If those people only have one person who loves and cares for them, then we’re talking about 50 per cent of our population living with dementia,” he explained.

There are two necessary steps, he continued: first, reducing the stigma associated with the disability, as he defines dementia, and change the narrative from despair to hope; and second, creating a public and private physical design and physical planning approach to reduce the excess disability that mis-fitting environments create.

“The problem of the stigma is that people are so afraid of dementia and people with dementia that the public narrative is one around despair,” he explained. “We must respect the rights of people with dementia. Dementia is not a disease; it’s a disability.”

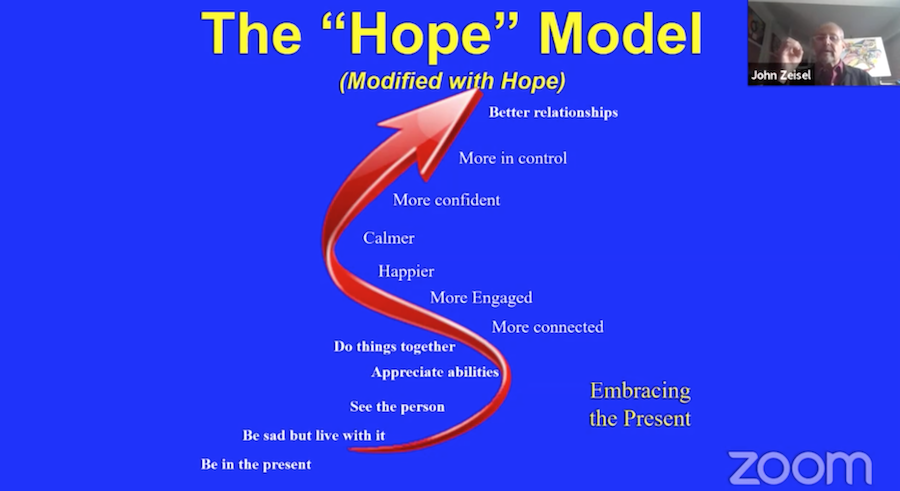

And the idea of “hope” is not that there will be a cure but that through hope, a life worth living for people with dementia can be provided.

Said Zeisel: “We put people in facilities and abandon them, and the four ‘A’s of anxiety, apathy, aggression and agitation increase. The hope model is that we are sad that there is dementia but we embrace the present, we stay engaged, we stay confident, and we do things together in the city. We have a city and society that embraces us and we have a continued relationship.”

To realise this vision, the city, he said, must provide five things: exercise, diet, sleep, reduced stress, and purpose and meaning.

Pointing to his contribution to Alzheimer Disease International’s recent report, Zeisel explained how he and his colleagues came up with a scheme for quality design and supportive design for people with dementia. The four-part scheme has two parts: one involves using design to overcome disease; the second is talking about a disability, not a disease.

“The scheme starts with the goals of wellbeing and dignity and respect, moves into principles of design, and the design approaches and responses are what architects and planners can do to respond to these principles, he said. “The Dignity Design Dementia Manifesto, available online to sign, includes the goals, values and principles, which our ADI report promotes as the way to integrate people to create supportive environments for people with dementia.”

Persons living with dementia require respect for their dignity, autonomy, independence, equality of opportunity, and non-discrimination, he added. “These are the goals and I believe these are the goals of a healthy city for all.”

He concluded: “We all need to have these emotional needs met, and engagement is one that is needed. Therefore, we need to create engagement places in the city. The designed environment can support and contribute to engagement for healthy cities for all.”